This is the first in a series of posts that pose the question, ‘Can you be a Christian and..?’ It seems to me that certain ways of being are incompatible with religious belief. Any religious belief, that is, though here I’ll limit myself to the Christian faith as that’s the belief system I know best and the one on which I wasted a great deal of my life.

Conversion is, I’ve become convinced, an emotional response to being told God loves you (who doesn’t want to be loved?) and that Jesus sacrificed himself so that you – yes, you – can enter into a full and meaningful relationship with God. It’s an intuitive, gut-reaction to the ‘promise’ that once you’ve accepted Jesus as Lord and Saviour, he will be with you always, guiding you through life and guaranting you’ll survive death.

What is rational about this? Nothing; it’s muddled supernaturalism, magic based on others’ dreams and visions, that appeals to your need to be wanted, to matter and your hope that your life means something and will go on beyond death.

The rationalisation comes after you’ve made this response and after your commitment. It’s rather like buying something incredibly expensive you’re not sure you actually need but which makes you feel good momentarily as you hand over your cash. On the way home, as doubts start to assail you, you start trying convince yourself that you were right to buy it, on the basis you deserve it, so that by the time you’re home you feel completely justified. Psychologists tell us we do this often: act first and then come up with the rationalisation for why we’ve behaved the way we have.

So it is that once you’ve made the emotional response to what Christianity purports to offer, you start justifying your decision to yourself. You know there’s really no evidence for what you’ve started to believe. All there is is the bible and other people’s enthusiasm for what it teaches, but still, there must be some sort of justification for it; all those others, including the guys who wrote the bible, can’t all be wrong. You’re helped in your rationalisation of the irrational by sermons in which a respected pastor explains what certain teachings mean, the warm and fuzzy feelings you get from fellowship with other Christians and from reading the bible with the aid of a study guide that smooths out its many inconsistencies and contradictions. You start reading too those devotional books that have been recommended to you, which give your new-found faith a respectable gloss. All after the event.

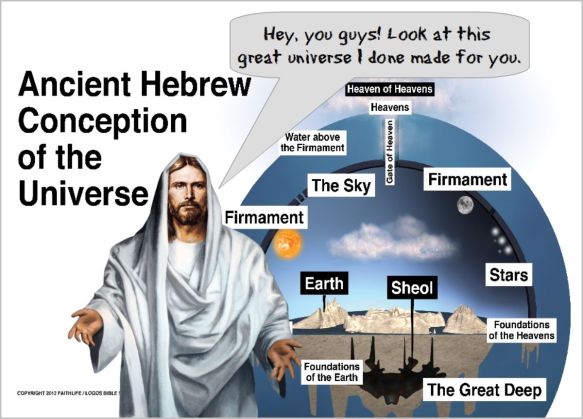

And before you know it you are fully invested in an entirely new belief system. Not only have you accepted the central mystery (magic) of salvation but you find yourself entertaining the notion that there exist all manner of supernatural beings; angels, demons, devils, spirits all engaged in spiritual warfare in higher places. You convince yourself, even when your intellect is telling you to exercise caution, of the existence of Heaven and Hell. You become persuaded that talking to yourself inside your head is communicating with the God of the Universe and that your very thoughts can change his mind. You assume what you are told is biblical morality and alter your world view so that it conforms to the bible’s: sin everywhere, yet miracles happen; God creating humans and not just (or even) evolution; Jesus returning at any time soon to change the word so it is more to your liking.

Yet there is no evidence for any of this. A book written by Iron Age tribesmen and first century religious zealots is not evidence. Nor is any of it rational. You know this, but you hold fast to your belief that God’s ways are not our ways. He likes, it says somewhere in the bible, to conceal his plans from the worldly wise. Like many other believers you are not stupid but you’ve happily sublimated your intellect to assume irrational, unsupported beliefs. You’ve subjugated your capacity for rationalisation in deference to these beliefs. If and when a rational objection forms itself in your mind, you dismiss it as a doubt, or worse still, a Satanic attempt to snatch you away from your salvation.

How do I know? Because I did so myself.

So, can you be a Christian and rational thinker? No. Because once you’ve tethered your intellect to ancient superstition you’ve denied yourself the possibility of independent thought. Rational thinking can go then in only one direction, towards the conclusions already established by the Faith. It isn’t possible to be an independent thinker and to adopt a worldview based on others’ emotions, dreams and visions. It isn’t possible to believe irrational things and be a rational thinker.