If you have read even a small percentage of my posts then you know I focus a great deal on defining and presenting the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ. I also focus on the Word of God as our source of God’s Truth, which is absolute. We also have defined faith and what God has done to save His people from their sins, which is the purpose of Jesus’ incarnation, perfect life, crucifixion, and resurrection.

Mike Ratcliff on Possessing the Treasure

Is your job description at work expressed as a story or myth?

Are the aims and objectives of your company based on the hallucinations of the owners?

Is the health and safety policy made up of spells and incantations devised by someone with no real connection to the company?

Can you imagine if the kind of documentation that determines your work conditions was composed of myths, stories of dreams and visions, historically unreliable accounts and largely incomprehensible, magical terms and conditions? Not only this, but you’re required to root around within this documentation to discover what it is you’re meant to be doing and when you have, you need to find someone who can explain it properly to you.

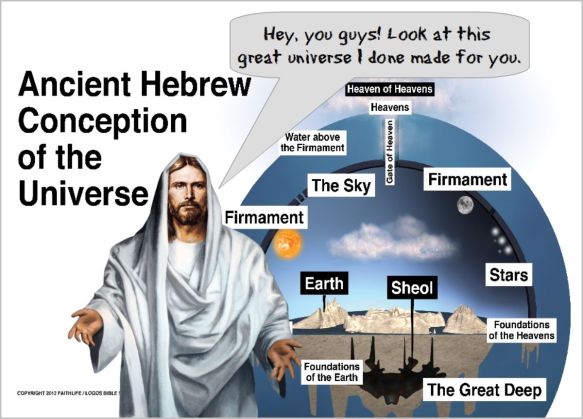

This, according to Christians, is how God chose to tell his creation what he expected of it. The omniscient, all powerful creator of the universe, whose thoughts are so much greater than ours, was unable to put together a clear, systematic and concise set of directions about how he wants us to live and what we should believe if we’re to avoid an eternity of torture.

These messages are so important, apparently, that he thought they’d be best conveyed in folklore and myth – much of it plagiarised from other cultures – fantastic stories written decades after the events they relate, and muddled, contradictory theology.

Why on Earth would he do this? Why would he not speak directly and clearly to fallible, sinful humans? Provide us, perhaps, with a list that sets out straightforwardly and unequivocally what we need to do if we’re to be ‘saved’. (It’s not as if he’s averse to supplying lists; the Ten Commandments are a list, as are the rules in Leviticus about beating slaves and what should and shouldn’t be eaten.) Why not communicate with us so that we know it’s him and not, say, some pre-scientific tribesmen or a bunch of superstitious zealots? Why not speak to us in ways that are not identical with the way we ourselves invent stories about imaginary beings and far-fetched events?

Why provide us with a ragbag of myths, legends and fables crammed with confused and inconsistent ideas, all of them created by those same fallible, sinful human beings, and stitched together, eventually, by a committee with a vested interest in the success of such a book?

It’s a mystery. Unless of course there’s no God behind the bible. Maybe that’s why we have much better policy documents at work.