To arrive at the nativity story most of us grew up with and which your kids and grandkids might well be performing this Christmas (mine are), the one with a stable, shepherds and wise-men, involves some cunning sleight of hand, not to mention a liberal dollop of invention.

The biblical ‘account’ of the story is spread across two gospels, Matthew and Luke. Mark hadn’t heard of it when he wrote his gospel so you won’t find it there. In fact, Mark’s Jesus doesn’t become God’s son until his baptism. Paul, writing earlier still, thinks God adopts Jesus only at his resurrection. Paul has no knowledge either of the nativity myth. John has no time for it: his Jesus is an eternal being who has existed with God from the beginning.

For Matthew, however, Jesus comes into existence when the Holy Spirit impregnates a virgin. Luke likes the idea and so copies it into his gospel. And now we have a problem: the idea that a virgin will bear the Messiah is lifted from the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Jewish scripture, which renders Isaiah 7:14 as –

Therefore YHWH himself will give you a sign: the virgin (almah) will conceive and give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel.

In the Septuagint, the Hebrew word almah, meaning ‘young woman’, is translated as virgin. However, the word for virgin in Hebrew is betulah, an entirely different word. Isaiah 7:14 is not a prophecy that a virgin will bear a son: only that a young woman will do so; in other words, a commonplace event. Matthew allowed himself to be misled: in his eagerness to find prophecies of Jesus in Jewish scriptures, he alighted on a mistranslation. He wrote his story accordingly, riffing freely on the error. Luke picked up on it a decade later, adding his own embellishments.

Neither does Isaiah 7:14 suggest the child being talked about will be the Messiah, nor that he will appear hundreds of years in the future. As subsequent verses make transparently clear, a short period of time is all that is suggested; no more than a few years:

He (the child) will be eating curds and honey when he knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right, for before the boy knows enough to reject the wrong and choose the right, the land of the two kings you dread will be laid waste. YHWH will bring on you and on your people and on the house of your father a time unlike any since Ephraim broke away from Judah – he will bring the king of Assyria (Isaiah 7:15-17).

These are all events contemporaneous with the writing of this part of Isaiah. All that is being said is that a young woman will become pregnant and produce a child in the near future. Even before this child properly knows right from wrong, YHWH will bring Israel’s enemies down upon it. (Because he’s such a caring God.)

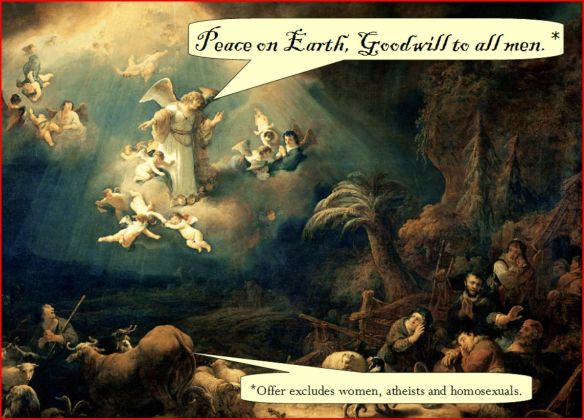

None of this has anything to do with a virgin becoming pregnant, nothing to do with a Messiah, nothing to do with Jesus. It is not a prophecy about him, even if Matthew persuaded himself it was. Shamefully, almost all modern ‘translations’ of Isaiah retain ‘virgin’, when they know perfectly well it is not the word used, and that the context neither supports it’s use nor makes it necessary. They do so to maintain the lie that Isaiah 7:14 is about Jesus and to give credibility to Matthew and Luke’s ridiculous fiction that he fulfilled ‘prophecy’ by being born of a virgin. It’s a deception that will be repeated in church services around the world over the next couple of weeks.