Aka The Death of Ananias by Raphael (Acts 5)

What was original Christianity like, long before it acquired that name? Before Paul’s ideas took hold? Clearly the cult existed prior to Paul. He tells us so himself: worship groups were around – the one he writes to in Rome, for example – before he established his own.

The early faith seems to have emanated from the visions of early believers such as Cephas and James. Quite what they ‘saw’ is open to debate but it led to them setting up a sect within Judaism that focused on the saving power of a risen celestial being.

And everything was absolutely hunky dory within these early communities. Members shared all their possessions (except when they didn’t, in which case they were annihilated on the spot) and lived in perfect harmony together, worshipping Jesus and experiencing miracles on a daily basis.

According to Acts, that is. According to Paul, by the time he came to be involved, it was all very different. Many of the early ‘churches’ were characterised by squabbling, greed, legal disputes, confusion about doctrine, sleeping around, visiting prostitutes and power struggles (Galatians 5.20; 2 Thessalonians 3.14-15; 1 Corinthians 1.10, 4.21; 1 Corinthians 6.1-10; 1 Corinthians 6.12-20; Galatians 1.6-9; 1 Corinthians 5.9-13 etc.) Worse still, there were defections by converts who came to their senses and left the cult.

How can this be when, according to Paul these people were inhabited by God’s holy spirit and saved once and for all by the redeeming blood of Jesus? Just as today, early believers, including Paul, had a hard time explaining how a person could be once saved and then lose their faith. They came up with various excuses how this could happen:

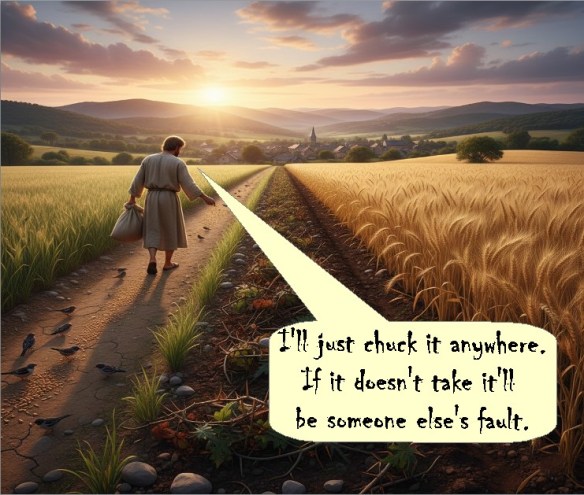

Excuse #1. Apostates were never really been saved: they were faking it in some way, their faith hadn’t been deep enough or Satan had snatched it away from them. One enterprising and influential cult member even came up with the sneaky idea of putting these explanations into the mouth of Jesus (because of course he would have foreseen the problem.) So arose the parable of the sower. According to Mark 4.1-20, the ‘word’ doesn’t always ‘take’. It might seem as if it has but sometimes it is uprooted by the cares of this world. Alternatively, it falls on stony ground and really doesn’t stand a chance of growing. Or Dick Dastardly Satan intervenes and destroys the faith of those who once believed. As a cultist called John later put it,

They went out from us, but they did not really belong to us. For if they had belonged to us, they would have remained with us; but their going showed that none of them belonged to us… (1 John 2.19)

Which really says nothing: ‘they left, so really they weren’t part of our gang to begin with.’ A brilliant bit of exposition.

Excuse #2. Apostates are still saved. In direct contradiction of the parable of the sower, some Christians invented a different way of accounting for those who had ‘fallen away’: the ‘once saved always saved’ argument, based on a few cherry-picked bible verses. Despite appearances, those who’ve left the faith are nonetheless still saved. The ‘reasoning’ is that because salvation is a work of God, it cannot be undone, no matter how much one refutes the faith, or provides reasons for leaving it or demonstrates the untruthfulness at the heart of it. Salvation is like a tattoo you regret getting but with which you’re stuck for the rest of your existence. (Except not really, for a whole host of reasons but principally because there’s no God to work the magic in the first place.) This line of reasoning runs entirely contrary to the acknowledgement in the parable of the sower that there are always those who will leave the faith.

Excuse #3. Apostates have been hurt by the church and as result have abandoned the faith (but Jesus is waiting for them to return!) While I don’t know anyone who has renounced Christianity for this reason alone, it does play a small part in some defections. Why? Because self-serving and vindictive Christians are evidence that Christianity simply doesn’t work. It doesn’t make ‘new creations’, infusing people with a holy spirit that makes them better people. Believers, despite their claims, are no more moral than those who are unsaved. You’ll know this if you’ve been on the receiving end of Christian judgment or condemnation. When Christians themselves undermine the claims of their religion it creates a justifiable scepticism in one-time brothers and sisters.

Excuse #4. Apostates just want to wallow in sin. Back to the parable of the sower for this one: ‘Satan has ensnared you into life of sin and debauchery and you have abandoned the one true way’. I have to say this is not true of any ex-Christians I know. They’ve dispensed with the wholly religious idea of ‘sin’, and now live their lives as authentically as they can, looking after their loved ones and helping others where possible. Then again, so what if people want to wallow a little bit?

The one reason that causes others to leave the fold that is never recognised by Christians is the gospel itself. No sir. That some people are able to see how irrational, contrived and downright untrue it is, is not a possibility Christians are willing to entertain. Jesus himself, however, seems to recognise that some people are just too intelligent to go along with it:

I praise you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children (Matthew 11.25).

Even he knew – or, far more likely, the sect that put these words into his mouth – that for anyone capable of a modicum of critical thinking (‘the learned and the wise’), the cult’s claims simply don’t stand up to inspection.