Somehow this repost unposted itself after the first few comments. I’m reinstating it and will post something new soon.

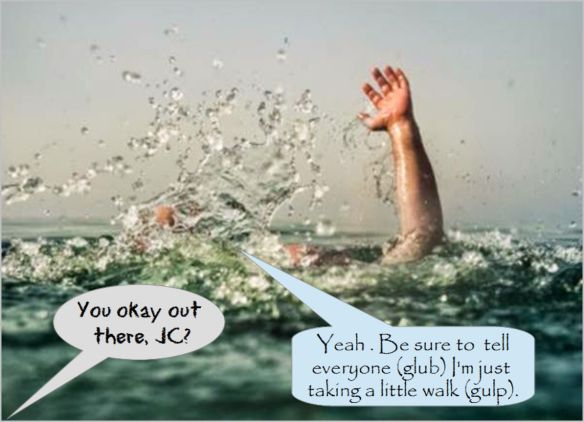

Don thinks I ‘exaggerate’ when I bring up what the New Testament says are supposed to be the direct consequences of the resurrection. As he seems to have no knowledge of the things Paul and others promised would follow, I offered to provide him with chapter and verse. The easiest way to do that is to republish this post, slightly amended, from 2018. (Alternatively, there’s this rather more flippant take on the subject.)

I’m willing to bet Don now tells me I don’t know how to interpret prophecy like an ancient Jew would, that the promises are really metaphors and despite being written for members of the nascent cult they’re really meant for people thousands of years in the future.

The Christian faith rests entirely on the resurrection of Jesus. As Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15.17 & 19:

…If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ are lost. If only for this life we have hope in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied.

Of course neither Jesus nor Paul’s invention, the Christ, were raised from the dead; those encounters with him, described in the gospels are, like Paul’s, visions and sensations of his presence (later ‘the Holy Spirit’) embroidered in the 40 or more years between when they occurred and when they were recorded.

Let’s though, suppose that Jesus really did rise from the dead and work backwards from there. What difference did it make? More specifically, what does the bible say were the results and consequences of Jesus being raised?

The Coming of the Kingdom

According to the New Testament (Matthew 25.34; Romans 15.12; Revelation 20.4-6), the resurrection was a clear sign that the Final Judgement and Yahweh’s Kingdom was finally arriving on Earth. Jesus is made to predict it:

Was God’s wonderful reign established here on Earth back in the first century? Was there a final judgement then? Were all wrongs righted, the social order inverted, and war and suffering abolished (Mark 10.31; Matt 5.2-11; Rev 21.4)? New Testament writers believed that following the resurrection, all of this would be happening –

in reality, none of it happened; not then and not since.

The Resurrection of the Dead

Did Jesus’ resurrection result in even more people rising from the dead? Paul said it would; he said Jesus was the ‘first fruits’, meaning the first of many, with others following him in being raised from the dead (1 Corinthians 15.20-21). Has any ordinary person – anybody at all – ever returned from the dead, long after they passed away? Not one; never mind the hundreds or thousands Paul and other early cultists had in mind. No Pope, no shining example of Christian piety, no activist or worker in the Lord’s vineyard has ever been resurrected during Christianity’s entire history. The dead have always remained stubbornly dead.

So no, this didn’t happen either.

New Creatures

Did the resurrection result in those who believed becoming ‘new creatures’? Paul said it would (2 Corinthians 5.17). He also said members of the new cult would be loving, forgiving and non-judgemental (1 Cor 5.12 & 13.14). There’s no evidence, from his letters, that they were, nor is there evidence from the long and often cruel history of the church. Christians today don’t always radiate loving-kindness either. Those who are caring and gentle before they become Christians remain so; those who are self-gratifying, vindictive or exploitative find a new context in which to be so. As I’ve said before, religion is like excess alcohol; it exaggerates the essential characteristics of a person, for good or for bad.

What it doesn’t do is make shiny ‘new creatures’.

So, what conclusions can we draw from this? Perhaps that nothing went to plan in post-resurrection Christianity. The promised results all failed to materialise. If the effects of the resurrection were and are not what they should have been, what does this say about their supposed cause?

If a storm is forecast and yet, when the time comes, there is no rain, wind or damage, wouldn’t we say that there was no storm?

If a woman said she was pregnant but during the ensuing nine months there was no physical evidence of pregnancy and ultimately no baby, wouldn’t we say she wasn’t pregnant at all?

If God’s Kingdom on Earth, brand new creatures, the resurrection of ordinary believers and the final judgement failed to materialise, wouldn’t we say there can have been no resurrection? The supposed causal event of all these non-effects really can’t have happened. Jesus died and like all dead people stayed dead. The visions, dreams and imaginings of his early followers gave rise to a cult in his name, one that, ultimately failed on all levels to deliver what it promised.

There was no resurrection.