I wonder what are the reasons those of you who were once Christians gave up on faith? Believers who know me far better than I know myself have attributed to me a whole range of motivations. Here’s a top ten of the reasons I rejected Jesus according to these spiritually astute know-it-alls:

In at 10 it’s…

You must have been hurt/had a bad experience of Christians. To which I answer, not particularly, though I did find the people I encountered in churches to be much like those I encountered in any other organisation I’ve been involved with. No different. Certainly no better, and in some ways worse when they squabbled or were petty and judgemental. Not sufficiently worse to make me abandon faith, but perhaps enough to make me ask whether Christianity really ‘worked’. Shouldn’t Christians who are new creatures, reformed in the image of Christ. be so much better than the rest of us?

At 9… You went to the wrong church. If so I must’ve attended several ‘wrong’ churches as I moved around the north of England with work. My wife and I always sought out churches with sound biblical teaching, so it wasn’t the lack of solid food that caused me to backslide (to use the Christian jargon.)

8. You wanted to wallow in your own sin. As I’ve said facetiously before, I like a good wallow as much as the next man and preferably with him. Back in the days of my struggling with faith, however, I didn’t find myself drawn to ‘sin’. I was trying to raise three children, do a demanding job and deal with the fallout from my boss’s affair with a colleague. My own sin was the last thing on my mind.

Related to this is the accusation that an apostate such as I wants, in some unfathomable way, to be God. Certainly I want to be fully human and to take charge of my own life, but aren’t these laudable intentions? It doesn’t mean I aspire to be God; I don’t want to be worshipped, don’t want to laud it over others, blame them for my deficiencies or send them to hell. That’s what God does, right? But it’s not me.

7. You rejected Christ because you’re gay and didn’t like the constraints faith placed on your sexual behaviour. See above. I didn’t admit I was gay until several years after I ditched faith and it was several more after that before I came out, yet more until I did anything about it. But okay, if you want to reverse the order of events, I gave up on religion because I was latently gay. But not really, though certainly the abandonment of faith was a liberation; I could think for myself and was free, over a long period of time, to finally become myself.

6. You read the wrong books. I certainly did: C. S. Lewis (I still have my collection of his books), John Stott, John Piper, John Bunyan, Bonhoeffer, Joni Erickson, Corrie Ten Boom, Billy Graham, David Wilkerson… and the Bible. So yes, I wasted a lot of time reading this sort of thing, but I’m guessing that’s not what my Christian accusers mean. I read more widely as I moved away from faith which helped me break out of the Christian bubble, but this wasn’t the reason I left the faith. I was well on the way by this time.

5. You were never a true Christian. Your faith was intellectual or habit or emotional but not deeply personal. Of course I was a true Christian. Just ask Jesus. Oh… you can’t. I’ve written about this before as you’ll see here. I was as real a Christian as those who claim they’re the real deal now.

4. You were in thrall to non-Christian writers. Not in thrall, no, but these writers – Ehrman, the so-called New Atheists, science writers (Dawkins’ science books particularly), Pagels, Barker, Loftus, Alter and, yes, Carrier – make a lot more sense than those who write from the perspective of faith. These authors don’t seem to mind, indeed they relish that their readers think critically about the evidence they present. Mumbo-jumbo isn’t passed off as erudition.

3. You have no awareness of the spiritual; you think that only that which can be measured is real. This is true, but it is not why I gave up Christianity. It is a consequence of doing so. I have seen no evidence of a spiritual realm that exists outside the human imagination. If anyone is able to present evidence that it does have independent existence, I’m open to it. Until then I will continue to live with the understanding that angels, devils, demons, heaven, hell, celestial saviours and gods, like unicorns, dragons and Shangri-La, do not exist. It follows that as non-existent beings they cannot communicate with us nor await us as our final destination.

2. Your heart has been hardened by Satan. See above; there is no Satan. Hardening of the heart is a metaphor for those who don’t fall prey to Christianity’s fraudulent claims or at last see through them.

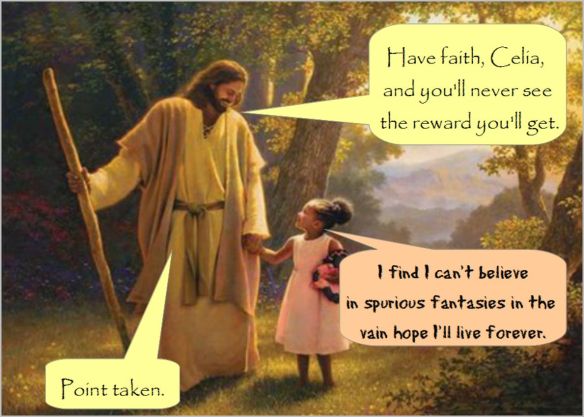

1. You gave up on faith because you realised none of it was true. Yes. Finally. This is why I rejected Christianity. It simply isn’t true, as I’ve attempted to demonstrate on this blog for the last 12+ years. Its third-rate fantasies, fake promises and failed prophecies are all evidence of its falsity.

But wait. None of the telepathic Christians who ‘know’ why I’m no longer a believer ever make this accusation. They would never concede that most (all) of what they believe simply isn’t true. But my life experience and my reading as I began to suspect Christianity was nothing more than a con have borne this out. Christianity is demonstrably untrue, theChristian God a fraud and supernatural-Jesus a fiction. This is why I abandoned Christianity.

How about you?

This is what what we’ve got so far:

This is what what we’ve got so far: