I thought we might share a couple of Bible studies these next couple of weeks. Some of you will remember these from your Christian days, when you’d gather with other eager believers so that a self-appointed expert could tell you what a particular story in the Bible really meant. I’m no expert, just someone who subjected myself to such indoctrination while all the time wondering if what I was being told was really what the passage was about. Doubts, however, were ‘of the devil’ so any such critical thinking needed to be suppressed. Since my eyes were opened to the allegorical nature of much of what is in the Bible and in the gospels in particular, I now see these same passages in a completely different light. I hope you’ll allow me to share my insights with you.

First off, it’s Mark 1:40-45, in which Jesus (seemingly) heals a leper:

A man with leprosy came to him and begged him on his knees, “If you are willing, you can make me clean.” Jesus was indignant. He reached out his hand and touched the man. “I am willing,” he said. “Be clean!”

Immediately the leprosy left him and he was cleansed. Jesus sent him away at once with a strong warning: “See that you don’t tell this to anyone. But go, show yourself to the priest and offer the sacrifices that Moses commanded for your cleansing, as a testimony to them.”

Instead he went out and began to talk freely, spreading the news. As a result, Jesus could no longer enter a town openly but stayed outside in lonely places. Yet the people still came to him from everywhere.

The giveaway phrase here is ‘make me clean’. The man does not ask Jesus to heal him which, suffering from a debilitating disease as he was, would have been the most obvious, most pressing request to make. Instead, he asks to be ‘cleansed’ with all its ritual connotations, the word used here, καθαρίζω (katharizo), also meaning ‘purify’. According to Leviticus 4: 11-12, leprosy was a condition that was spiritually unclean. Only by making the prescribed offerings – the usual doves, lambs and ‘crimson stuff’ – could a leper who was already healed become ritually pure.

Who, according to the New Testament, replaces all the sacrificial offerings of the old covenant? Why, it’s Jesus himself of course (1 Corinthians 11:25, Ephesians 5:25-26 etc). Jesus cleanses and purifies the leper in the story, just as he is able to cleanse and purify sinners. This is what the early cult believed: ‘Ask Jesus, the heavenly Christ, to cleanse you of your sins and, just like he does for the leper in this parable, he’ll do it for you. As a penitent believer, you are the leper. Not only are you cleansed of your sin, you are purified.’

This also explains why Jesus is ‘indignant’ when the leper first approaches him. On the surface it makes little sense for him to be indignant with the man, which is why some translations change this verse to say Jesus ‘felt compassion for him.’ Jesus’ metaphorical annoyance is for those who have allowed the man’s spiritual condition to have deteriorated to a state comparable with leprosy. The Jewish priestly system, symbolised anachronistically in Mark as the Scribes and Pharisees, the later arch-enemies of the new cult.

Jesus commands the leper to visit the Jewish priest to demonstrate that he, Jesus, is the new cleanser of sins, replacing the priesthood itself. Instead, the leper goes against Jesus’ and the early cult’s wishes. My God, how could the cult remain secret and exclusive if newly cleansed converts behaved like this!

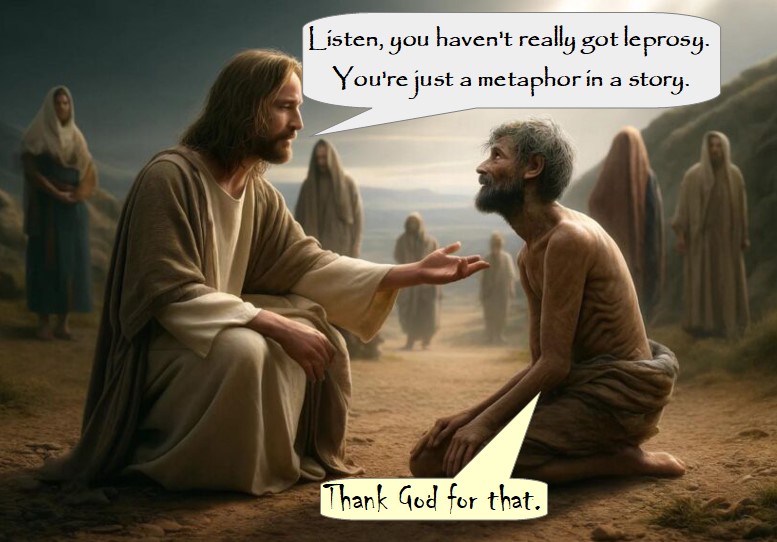

So there you have it. The leper is a metaphor for the sinner in need of the heavenly Jesus’ cleansing. His leprosy is a metaphor for the sin itself. The healing is a metaphor for the penitent’s spiritual purification. The man’s by-passing of the Jewish law is a metaphor for Jesus replacing the law. The cleansed leper’s shouting about it is a metaphor for the early cult’s desire to keep its rituals and teaching secret. Its parables like this one were designed to enlighten cult members while obfuscating and confusing the unbeliever (Mark 4:11-12).

As a literary creation, an allegory replete with metaphor, this event need never have happened in reality. Given its literary nature, it’s highly unlikely it did.