Those opposed to the idea that Jesus was only ever a mythical figure are generally dismissive of those who point to the evidence of the New Testament that this is precisely how the earliest Christians saw him. These critics lambast as ‘amateurs’, ‘pseudo-historians’ and ‘fringe’ enthusiasts those who don’t see any evidence for an historical Jesus. But such ad hominems are not arguments and they’re certainly not evidence that a human Jesus existed. When the books of the New Testament are arranged in chronological order, the very earliest writing about Jesus – Paul in the 50s and the creed of 1 Corinthians 15 – appear to view him only as a scripture-fulfilling spiritual manifestation.

So, was Jesus actually an itinerant preacher who traipsed the Earth in the 30s before rapidly evolving into Paul’s mythical Christ or was he a mythical being to begin with, only later to be cast as an historical figure?

It has to be one or the other.

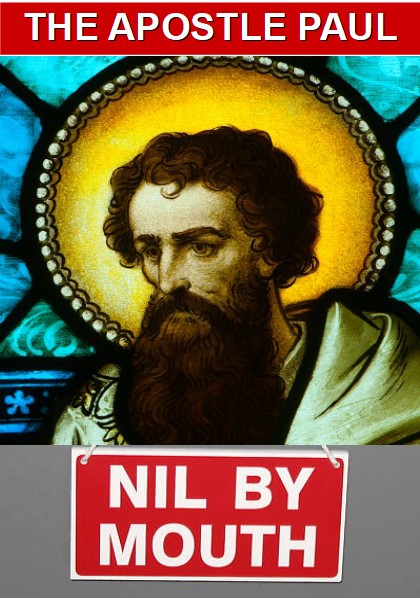

Within twenty years of his supposed death, Paul and others had experienced dreams, visions and hallucinations (Acts 2:17) that convinced them Jesus was a supernatural being in heaven. This doesn’t of course rule out that a human Jesus had actually existed, but it makes it unnecessary for him to have done so. Paul and almost all the creators of the New Testament books treat his earthly existence as irrelevant. Even when ‘proving’ their celestial Superman is the promised Messiah, they refer not to his activities on Earth, but appeal exclusively to what they believed Jewish scripture revealed about the Messiah.

According to these men, this is how they knew the Jesus of their dreams was truly the Saviour: the ancient scriptures. Not a single one of them says, ‘I refer you to Jesus’ miraculous birth in Bethlehem; I remind you that he changed water into wine, controlled the elements and miraculously multiplied food.’ Not one of them references his many healings, exorcisms and raising of people from the dead. Not one mentions the historical details surrounding his crucifixion, the empty tomb or the women who first saw him alive again. Not one relates a single resurrection appearance (beyond their own visions) nor do they mention the ascension or a looked for ‘second’ coming. Why not? Surely these would be the definitive indicators that Jesus was the Messiah, instead of, or at least alongside, the so-called prophecies of ancient scriptures.

The ‘why not?’ is because these stories – the birth, the miracles, the healings, the empty tomb, the bodily resurrection, the ascension and the rest – had, at the time Paul was writing, not yet been created. Consequently, they couldn’t be passed on to Paul when he met Cephas and James. There was no much-vaunted ‘oral tradition’ for him to call upon to fill in the gaps in his knowledge about an Earthly Jesus. There was no oral tradition because there was no Earthly Jesus to relate stories about when Paul was active in the 50s. This version of Jesus, created from Jewish scripture, Paul’s teaching and cult rules, didn’t appear until the early 70s. Even after Mark’s gospel and its copycat sequels, most of the writers of later New Testament continued to believe in and refer only to a heavenly saviour verified by ancient Jewish scripture.

But, apologists say today, no-one at the time would be taken in by talk of a Messiah who existed only in the heavenly realm. And that’s true; despite the Bible’s claims to the contrary, very few people were persuaded. But some bought into it, just as others at the time bought into Mithras. Mithraism was, for a while, more successful than the fledgling Christian cult. Yet its adherents knew Mithras himself manifested only in the heavenly plane. This didn’t stop multitudes of military men from joining the cult to worship him. It was the same for the other deities of the day. They too didn’t exist even if stories about their adventures on the Earth were widely circulated and, in all probability, believed by the gullible.

If, however, Jesus’ life on Earth had happened in the early part of the first century, how was it that 20 years after his death he had already become an angelic being without a past? Why had Paul, the writer of Hebrews, the pseudo-Pauls, James and John of Patmos never heard any of the stories about him, or didn’t care about them or felt they weren’t really evidence of Jesus’ Messiahship? Where are those stories? Outside the later gospels they don’t exist. It’s as if, when Elvis Presley died, no one cared any more about all the hit records he’d made and were instead only interested in his post-mortem sightings in laundromats and shopping malls. The process just doesn’t happen this way round.

No, it is far more likely that Jesus went from being a celestial saviour to having stories written about him, stories that are based on prophecies in Jewish scripture and Paul’s ‘revelations’. They are allegorical and metaphorical, wholly made up as the writer of Mark 4:11-12 tells us with the equivalent of a Clark Kent wink:

The secret of the kingdom of God has been given to you. But to those on the outside everything is said in parables so that ‘they may be ever seeing but never perceiving, and ever hearing but never understanding; otherwise they might turn and be forgiven!’

This is what what we’ve got so far:

This is what what we’ve got so far: