Much is made of the oral tradition that it is said informs the material in the synoptic gospels, and possibly John too. The tradition of conveying the events of Jesus’ life and the things he said goes back to Jesus’ original followers – the disciples and the apostles (the terms are not necessarily interchangeable) – and continues with a high degree of accuracy, at least until AD70 when the first gospel was written.

Which must be why we find so much detail about Jesus’ life in the letters of Paul, from his first letter, 1 Thessalonians, written circa AD55 to his last, Philippians (now an amalgam of several letters), written about 62. Paul was aware of the stories about Jesus – as all converts were – and affirms so many of the details of his life in his letters, passing on the vital stories and the traditions associated with him, in written form.

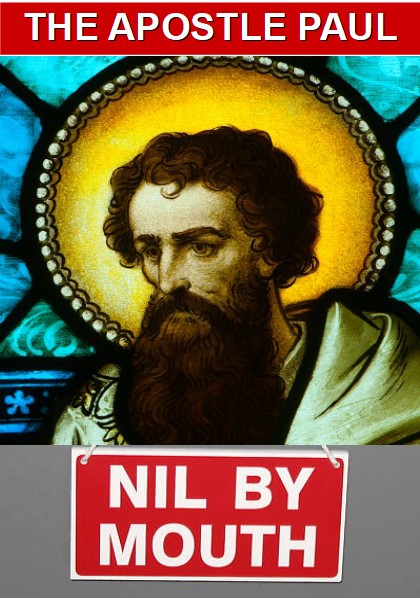

But not in our reality. Our Paul knows nothing of the details of Jesus’ life. Not once does he quote him or refer to the events of his life before the resurrection. There is nothing of the oral tradition. Nowhere in his letters does he draw from it; never does he say he knows for a fact that Jesus said or did a specific thing while on Earth.

Even after his meeting with Cephas and James, a full three years after his conversion, Paul relays not a single thing he learnt from them. After the encounter, he continues to promote only his own revelations and says nothing of what he learnt about Jesus from the man who supposedly spent three eventful years with him.

Fourteen years later, Paul meets again with Cephas and encounters other apostles for the first time. On this occasion, he and Cephas argue about justification and Paul comes away grumbling that ‘those leaders added nothing to me’ (Galatians 2:6) What? Not even stories about their time with the Master? Apparently these weren’t as important as disputes about soteriology.

Later still, Acts tells us that immediately after his conversion, Paul stayed with ‘disciple’ Ananias and other ‘disciples’ for several days. Did Ananias not know any of the oral tradition that he could pass on to Paul? Details about Jesus’ life, a saying or two or an account of a miracle? Apparently not. (This might be because the story is pure fabrication. Paul tells us himself, in Galatians 1: 16, that immediately after his conversion he ‘did not rush to consult with flesh and blood’).

Surely, though, he must have heard some of the Jesus story from those he persecuted prior to his dramatic conversion. If he did, he didn’t see fit to include any of it in his letters. Likewise, Paul had contact with cult communities he didn’t himself establish, such as that in Rome. Surely they conveyed some of the stories about Jesus that they had had passed on to them. He appears too to have known at least one other evangelist: Apollos. If these other believers did pass on stories of Jesus from an ultra-reliable oral tradition, why didn’t Paul see fit to include any of them in his letters?

So what were Paul’s sources? Certainly not the oral tradition, nor Q, the hypothetical sayings gospel, which he likewise ignores. If the gospel was being spread orally from the time Jesus lived, by the apostles and other preachers, and was being passed around the fledgling cult communities, why did Paul know nothing of it? If in fact he did, why did he choose to ignore it in favour of his own inner-visions? Did he consider it of such little value?

These questions matter, as we’ll see next time when Mark decides he’ll set the Jesus story down on paper.